The album cover of the guitarist Eric Clapton’s “One more car, One more rider”

In the realm of scientific software development, many programmers lack a strong background in computer science. This particular niche emphasizes expertise in areas such as physical modeling, numerical methods, applied mathematics, and high-performance optimization. As a result, most practitioners in this community tend to stick to the familiar procedural programming approach. However, when faced with the concept of “objects” in object-oriented programming, newcomers often encounter questions like whether they should use objects, if they offer advantages over procedural approaches, how to implement them effectively, and what potential pitfalls to watch out for. Unfortunately, the answer to these questions is often ambiguous and depends on the specific situation.

If you cannot afford to dive deep into computer science just yet, we’ll attempt to provide a brief overview of this issue with an example in ten minutes… with a guitar.

Too Long; Don’t read

This text emphasizes the importance of focusing on how to use a function or object rather than its internal implementation. This approach aligns with the dependency inversion principle, which suggests that the code’s usage should be prioritized, and implementation details can be addressed later. Developers should collaborate closely with beta testers to refine the final usage (or Application Programming Interface,API ), especially if they are considering advanced programming concepts.

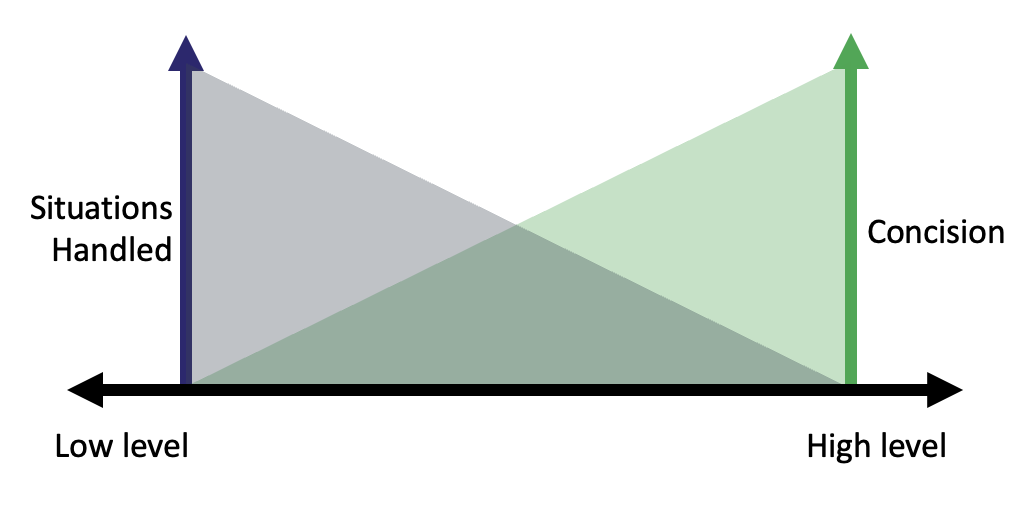

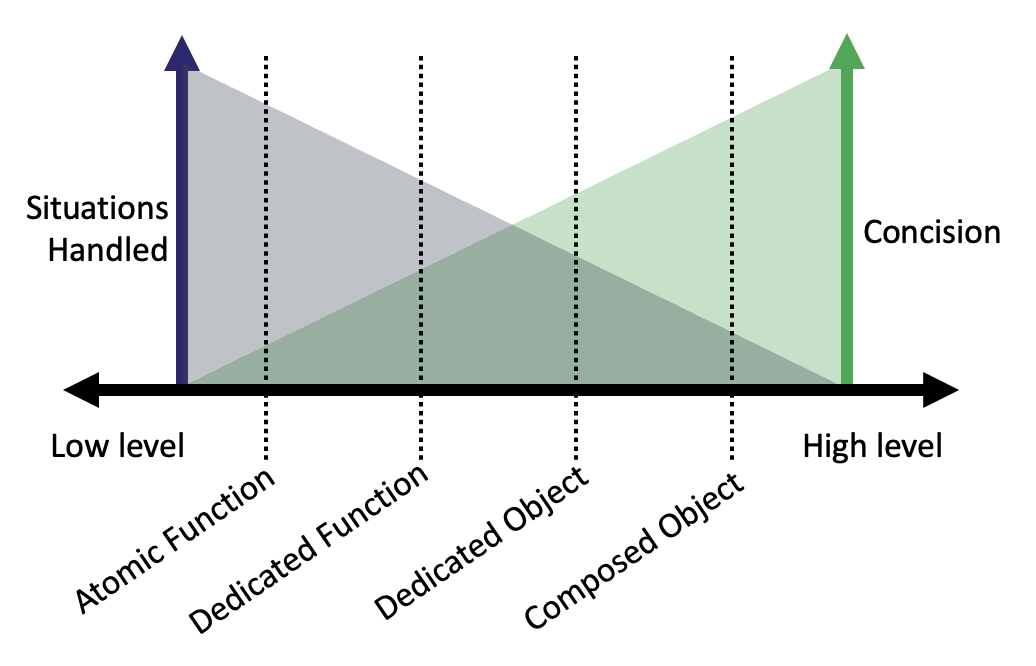

The text also discusses the trade-off between multi-purpose APIs with verbose explicit calls (low-level) and case-specific APIs with very concise calls (high-level). To cater to different user needs, it advocates for progressive APIs that incorporate both functional low-level functions and specialized high-level objects. This allows users to choose the level of abstraction that suits their requirements.

The fewer situations an Application Programming Interface have to handle, the more concise it can be. The developer must weight how much the code should be specialized.

All the code presented here can be downloaded from gitlab.com here.

A brief intro to Object oriented Programming

Object-oriented programming (OOP) is a programming paradigm that organizes code around objects, which are instances of classes. It promotes encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism for modular and reusable code. OOP originated in the 1960s with Simula and gained popularity through languages like C++ in the 1980s. It has become a fundamental concept in modern software development, offering advantages such as code reusability, modularity, and easy modeling of real-world entities. It promotes efficiency, code organization, extensibility, and flexibility through encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism.

However, while object-oriented programming (OOP) has benefits like code reusability and modeling real-world entities, it can introduce complexity and overhead. Inheritance can lead to tight coupling, and OOP may not be suitable for all problem domains. Additionally, beginners may find it challenging, and an overemphasis on class hierarchies can result in inflexible designs.

Trying to play a song

Just one note

Now, shall we start a program with simple idea in mind:

Hey, can I make this computer play a note A440?

With a bit of net-surfing we get this:

import numpy as np

from sounddevice import play as sdplay

SAMPLING_FREQ = 44100

def pure_beep(

freq: int = 440, duration: float = 1.

) -> np.array:

"""

Generates a pure beep waveform with a single frequency tone.

Parameters:

freq (int, optional): The frequency of the tone in Hz. Defaults to 440.

duration (int, optional): The duration of the generated waveform in seconds. Defaults to 1.

Returns:

np.array: An array of generated waveform samples.

"""

amp=1.

t = np.linspace(0, duration, int(duration * SAMPLING_FREQ), False)

note = amp * np.sin(freq * t * 2 * np.pi)

return note

sdplay(

pure_beep(freq=440, duration=1.),

blocking=True,

samplerate=SAMPLING_FREQ)

It generates a pure beep waveform with a specified frequency and duration using the NumPy library. The pure_beep() function takes optional parameters for amplitude, frequency, and duration, and returns an array of waveform samples.

The sdplay() function from the sounddevice library is then used to play the generated waveform with a frequency of 440 Hz and a duration of 1 second. The blocking=True argument ensures that the program waits for the sound to finish playing before continuing. This is a simple way to generate and play a pure beep sound.

As a pure sine is quite horrible to hear, we can make it nicer with harmonics:

import numpy as np

from sounddevice import play as sdplay

SAMPLING_FREQ = 44100

def fat_beep(

freq: int = 440,

duration: float = 1,

) -> np.array:

"""

Generates a fat beep waveform with harmonics using additive synthesis.

Parameters:

freq (int, optional): The frequency of the fundamental tone in Hz. Defaults to 440.

duration (float, optional): The duration of the generated waveform in seconds. Defaults to 1.

Returns:

np.array: An array of generated waveform samples.

"""

harms=8

decay=0.2

amp=1.

t = np.linspace(0, duration, int(duration * SAMPLING_FREQ), False)

note = amp * np.sin(freq * t * 2 * np.pi)

for i in range(harms):

amp *= decay

note += np.sin((i + 1) * freq * t * 2 * np.pi)

return note

sdplay(

fat_beep(freq=440, duration=1.),

blocking=True,

samplerate=SAMPLING_FREQ)

This program extends the previous one by introducing a fat_beep() function that generates a waveform with harmonics using additive synthesis. It includes two new parameters: harms for the number of harmonics to include and decay for the decay factor applied to each harmonic amplitude. The result is a richer, more complex sound compared to the pure beep waveform.

If you search a bit on the web, you will probably discover the Karplus-Strong method used in old music synthetizers, to do the same:

def kpst_pluck(freq: int, duration: float=1.0) -> np.array:

"""

Generates a plucked string waveform using the Karplus-Strong algorithm.

Parameters:

duration (float): The duration of the generated waveform in seconds.

freq (int): The frequency of the plucked string in Hz.

Returns:

np.array: An array of generated waveform samples.

"""

resampled_sampling_frequency = int(SAMPLING_FREQ * (2.0 / duration))

wavelength_in_samples = int(

round((SAMPLING_FREQ / freq) * (resampled_sampling_frequency / SAMPLING_FREQ))

)

noise_samples = [random() * 2 - 1 for _ in range(wavelength_in_samples)]

output_samples = []

for _ in range(SAMPLING_FREQ * 2 // len(noise_samples)):

for output_position in range(len(noise_samples)):

wavetable_position = output_position % len(noise_samples)

noise_samples[wavetable_position] = (

noise_samples[wavetable_position]

+ noise_samples[(wavetable_position - 1) % len(noise_samples)]

) / 2

output_samples += noise_samples

exp_size = int(duration*SAMPLING_FREQ)

output=np.zeros(exp_size)

for i,val in enumerate(output_samples):

try:

output[i]=val

except IndexError:

pass

return output

sdplay(

kpst_pluck(freq=440, duration=1.),

blocking=True,

samplerate=SAMPLING_FREQ)

We have now three functions sharing the same signature:

function_name(freq: int, duration: float) -> np.array()

However their content differ a lot. One could be tempted to merge them, but right now, there is no need. Here comes the first tip:

I you have a good idea, always wait until your work asks for an implementation. jumping to the implementation right away is wrong in two ways:

- You procrastinate the critical stuff, delaying your work.

- It is a premature optimization, a code smell with plenty of drawbacks.

A song on one single string

Photo Gabriel Gurrola in Unsplash. A close-up of an acoustic guitar, with its six strings and twenty frets diviting the guitar neck.

We got the sound on, let’s build a guitar

We start with a simple riff on a single string: “Seven nation army” from the white stripes. Using the simplified tab notation, the song goes like this:

e |------------------------------------------|

C#|------------------------------------------|

A |------------------------------------------|

E |------------------------------------------|

A |--7------7--10---7---5--3--------2--------|

E |------------------------------------------|

Reading this is easier than you could think. First, there are numbers only on line “A”, meaning the song can be played on a single string tuned to the note “A”, the second one when you look at a guitar you are holding.

The standard tuning is :

| String | Freq | Pitch Notation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (e) | 329.63 Hz | E4 |

| 2 (B) | 246.94 Hz | B3 |

| 3 (G) | 196.00 Hz | G3 |

| 4 (D) | 146.83 Hz | D3 |

| 5 (A) | 110.00 Hz | A2 |

| 6 (E) | 82.41 Hz | E2 |

The number are positions on the fretboard called frets. There are 12 lines on the guitar neck dividing the string into 12 semitones. Being one semitone higher mean a frequency multiplied by 1.0595 (256/243 exactly). Therefore, the 7th fret of string A is 7 semitone higher than the tuning frequency : \(110 * 1.0595^7 ~= 164.81\), i.e the note E3. The position of each number is an approximation of when it should be played.

Now what we would like is a way to control the program close to this input:

time= 1 2 3 4

0123456789012345678901234567890123456789012

A |--7------7--10---7---5--3--------2--------|

We can try something like:

# create the necessary notes

n7 = guitar_string(fret=7, tuning=110., duration=1.0)

n10 = guitar_string(fret=10, tuning=110., duration=1.0)

n5 = guitar_string(fret=5, tuning=110., duration=1.0)

n3 = guitar_string(fret=3, tuning=110., duration=1.0)

n2 = guitar_string(fret=2, tuning=110, duration=1.0)

# create a 4.3 second long void song

song = create_base(duration=4.2)

# Declare the tab

song = add_note(song, n7, 0.3)

song = add_note(song, n7, 1.0)

song = add_note(song, n10, 1.3)

song = add_note(song, n7, 1.8)

song = add_note(song, n5, 2.2)

song = add_note(song, n3, 2.5)

song = add_note(song, n2, 3.4)

sdplay(song, blocking=True, samplerate=SAMPLING_FREQ)

Let’s build first plucked string function:

SEMITONE_RATIO = 256./243

def guitar_string(fret: int, tuning: float = 82.41, duration: float = 2.0) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Generate a plucked guitar string sound.

Parameters:

- fret (int): The fret number to play on the guitar string.

- tuning (float): The frequency of the string's initial tuning (default: 82.41 Hz for E2).

- duration (float): The duration of the generated sound in seconds (default: 2.0 seconds).

Returns:

- np.ndarray: An array representing the generated sound.

"""

# Calculate the frequency based on the tuning and fret number

string_freq = tuning * (SEMITONE_RATIO ** fret)

return kpst_pluck(freq=string_freq, duration=duration)

We add the functions to declare a void song, and a second to add notes on this base:

def create_base(duration: float) -> np.array:

"""

Create the base sampling array for a song.

Parameters:

duration (float): The duration of the base sampling array in seconds.

Returns:

np.array: A numpy array of zeros representing the base sampling array.

"""

return np.zeros(int(duration * SAMPLING_FREQ))

def add_note(base: np.array, note: np.array, start: float) -> np.array:

"""

Add a note to the base sampling array for a song.

Parameters:

base (np.array): The base sampling array.

note (np.array): The array representing the note to be added.

start (float): The start time of the note in seconds.

Returns:

np.array: A numpy array representing the updated base sampling array with the added note.

"""

id_start = int(start * SAMPLING_FREQ)

base_out = base.copy()

if id_start >= base.size:

return base_out

id_end = min(id_start + note.size, base.size)

base_out[id_start:id_end] += note[0: id_end - id_start]

return base_out

If you try these, you should be able to synthetize the first bar of “seven nations army”

How an object can show up

Objects are tools to simplify the Application Programming Interface (API). If you look are our current API, we have for example this section:

n7 = guitar_string(fret=7, tuning=110., duration=1.0)

n10 = guitar_string(fret=10, tuning=110., duration=1.0)

n5 = guitar_string(fret=5, tuning=110., duration=1.0)

n3 = guitar_string(fret=3, tuning=110., duration=1.0)

n2 = guitar_string(fret=2, tuning=110, duration=1.0)

There are a lot of repetitions. While the duration could be often changed to build a song, the tuning sould not. Moreover, it is only by looking at the tuning that we read it is the A string.

We can make this part of the API clearer like this:

string_A = GuitarString(tuning=110.)

n7 = string_A.pluck(fret=7, duration=1.0)

n10 = string_A.pluck(fret=10, duration=1.0)

n5 = string_A.pluck(fret=5, duration=1.0)

n3 = string_A.pluck(fret=3, duration=1.0)

n2 = string_A.pluck(fret=2, duration=1.0)

The string_A is an object GuitarString() set to 110Hz tuning. This is called an instance of the object. .pluck() is a method of the object which replaces the guitar_string() function. What makes this object unique is its internal information, the attribute tuning.

How do we get this object-maker GuitarString()? We define a class:

class GuitarString:

def __init__(self, tuning: float = 82.41):

self.tuning=tuning

def pluck(self,fret:int, duration:float=2.)-> np.array:

return guitar_string(fret=fret,tuning=self.tuning, duration=duration)

This class features an initialization (__init__()) method, and the wanted pluck() method. Methods are like augmented functions. Being defined in a class, they can use the attributes -here self.tuning- which are object-specific parameters

The API is closer to our story “let’s play a one string” song, and Yay! we made an object. But let’s see the dark side we introduced too.

The cost of an object : mental load

In our story, we looked at one bar of the song. If we are doing this on a larger program, the calls to foo.pluck() will be stored far from the instanciation foo=GuitarString(). Here, only a good descriptive naming (string_A) helps to identify what string is played.

Try to imagine now dealing , not with this nice guitar string, but with an abstract concept you never heard before today, like a “Base for Proper Orthogonal Decomposition on abritrary meshes” called base(). As a reader you will need to “learn” the concept before being able to understand the code.

These issues are unknown in the realm of pure functionnal programming, since the author is explicitely writing all inputs and outputs. Finally, both ways have weaknesses:

- Functionnal API, with many lines full of inputs, potentially very slow to read, which lead us to an object.

- Object Oriented API, with fewer lines and inputs repetitions, potentially coming with a large mental load, making functions desirable again.

A Chord-based song

Our popular songs are made of chords, i.e. group of notes played together. The harmony between the notes suggest emotions to the listener. Let’s try a chord-based song, with the first bar of “The House of the Rising Sun”, which loops over the progression Am,C,D,F.

| Chord | Plucks |

|---|---|

| Am | X02210 |

| C | X32010 |

| D | XX0232 |

| F | 133211 |

The guitar notation above, X0221O is a condensed version of the previous one:

| Name | code | Str. E | Str. A | Str. D | Str. G | Str. B | Str. e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Am | X02210 |

No pluck | No fret | 2nd fret | 2nd fret | 1st fret | No fret |

We must now play several strings at once.

Functional version

First, see this Am chord using functions:

# create the necessary notes

A_0f = guitar_string(fret=2, tuning=110.00, duration=1.0)

D_2f = guitar_string(fret=2, tuning=146.83, duration=1.0)

G_2f = guitar_string(fret=2, tuning=196., duration=1.0) B_1f= guitar_string(fret=1, tuning=246.94, duration=1.0)

e_Of = guitar_string(fret=0, tuning=329.63, duration=1.0)

# create the basis for the chord

chord_Am = create_base(duration=1.0)

# Add notes

chord_Am = add_note(chord_Am, A_0f, 0.0)

chord_Am = add_note(chord_Am, D_2f, 0.0)

chord_Am = add_note(chord_Am, G_2f, 0.0)

chord_Am = add_note(chord_Am, B_1f, 0.0)

chord_Am = add_note(chord_Am, e_Of, 0.0)

These ten lines are a bit verbose, but easily readable for one chord. However a real song involves easily 6 to 8 chords. This would mean 60 to 80 lines.

Using the GuitarString object

Now with the object we just created:

string_e = GuitarString(tuning=329.63)

string_B = GuitarString(tuning=246.94)

string_G = GuitarString(tuning=196.00)

string_D = GuitarString(tuning=146.83 )

string_A = GuitarString(tuning=110.00)

string_E = GuitarString(tuning=82.41)

# create the necessary notes

A_0f = string_A.pluck(fret=0, duration=1.0)

D_2f = string_D.pluck(fret=2, duration=1.0)

G_2f = string_G.pluck(fret=2, duration=1.0)

B_1f= string_B.pluck(fret=1, duration=1.0)

e_Of = string_e.pluck(fret=0, duration=1.0)

# create the basis for the chord

chord_Am = create_base(duration=1.0)

# Add notes

chord_Am = add_note(chord_Am, A_0f, 0.0)

chord_Am = add_note(chord_Am, D_2f, 0.0)

chord_Am = add_note(chord_Am, G_2f, 0.0)

chord_Am = add_note(chord_Am, B_1f, 0.0)

chord_Am = add_note(chord_Am, e_Of, 0.0)

Now we tune the 6 strings before the song, and never state a frequency again. There are however more lines because the code states more than just four frequencies. The API improvement is a bit lost now we are dealing with multiple chords.

Moving to a guitar objet

Let’s create an object more handy to play chords, starting again from the API:

guitar = Guitar([82.41,110.00,146.83,196.00,246.94,329.63])

chord_Am = guitar.pluck([None,0,2,2,1,0],2.)

chord_C = guitar.pluck([0,3,2,0,1,0],2.)

chord_D = guitar.pluck([None, None,0,2,3,2],2.)

chord_F = guitar.pluck([1,3,3,2,1,1],3.)

The Guitar object takes a list of tunings. Then the method .pluck() returns the addition of plucked strings.

With this solution, a 8 chords song would require 8 lines, plus the instrument tuning.

How could we implement this?

class Guitar:

def __init__(self,strings_tunings:list):

self.st=[]

for tuning in strings_tunings:

self.st.append(GuitarString(tuning))

def pluck(self, frets:list, duration: float):

note=create_base(duration)

for i,fret in enumerate(frets):

if fret is not None:

note +=self.st[i].pluck(fret, duration)

return note

This Guitar object stores only a list of GuitarString objects. Then its .pluck() methods superimpose the output of GuitarString.pluck().

In this example, we are using object composition: an object made of other objects.

This object is a bit fragile for now, since the user must take care of providing 6 items lists each time. This crudeness is also a good think because you could easily use it for a Bass or a Ukulele.

To play “the House of the rising sun” we can now try:

song = create_base(5)

song = add_note(song, chord_Am,0)

song = add_note(song, chord_C,1)

song = add_note(song, chord_D,2)

song = add_note(song, chord_F,3)

Observations on objects

Closer to a story means further from all the others

We created a very nice Guitar object to play chords. But how does it performs with our single string song?

guitar = Guitar([82.41,110.00,146.83,196.00,246.94,329.63])

n7 = guitar.pluck([None, 7, None, None, None, None], duration=1.0)

n10 = guitar.pluck([None, 10, None, None, None, None], duration=1.0)

n5 = guitar.pluck([None, 5, None, None, None, None], duration=1.0)

n3 = guitar.pluck([None, 3, None, None, None, None], duration=1.0)

n2 = guitar.pluck([None, 2, None, None, None, None], duration=1.0)

This new object, handy for chords songs, is a bit clunky for our “Sevens nation army”, with many repetitions of None standing for “do not play this string”.

We could of course extend the API of Guitar. A dedicated generic method like this would adapt to 4 or 6 or even 8 strings intruments:

n7 = guitar.single_pluck(7, string_index=1, duration=1.0)

However this argument string_index=1 is not really clear to specify the second string. We could instead create methods called upon the name of strings:

# Version 1 : dedicated method with string name

n7 = guitar.str_A_pluck(7, duration=1.0)

# Version 2 : object in attribute with string name

n7 = guitar.str_A.pluck(7, duration=1.0)

However setting in stone the tunings of strings means a great loss of flexibility.

In the end, it would be hard to create a Guitar able to deal nicely with the two situations without loosing flexibility nor readability.

Getting the best of everything : A progressive API

We have just seen our best object cannot be adapted to all situations, but this is fine : the guitar example provided several solutions to play sounds:

| Name | Type | Level | Situation |

|---|---|---|---|

Guitar() |

Composed object | High | Playing chords on a tuned instrument |

GuitarString() |

dedicatedObject | Middle | Playing on a tuned string |

guitar_string() |

dedicated function | Low | Playing on a string |

kpst_pluck() |

atomic function | Very Low | Playing a sound |

fat_beep() |

atomic function | Very Low | Playing a sound |

pure_beep() |

atomic function | Very Low | Playing a sound |

This API is “progressive”: new users can use it at high level while advanced users with better awareness have access to lower level functions. This freedom does not require duplicated code. Indeed, if you read the sources again, you will see each new level is build on top of the previous level.

Our four levels of APIs on the initial sketch. Nobody ever said a single solution should fit all needs.

Some common mistakes

Unnecessary statefulness

A statefull code means that some properties evolves during the call. As objects are, before anything, data storages, they often becomes stateful. See for example this scenario with a TunableGuitar() object:

# A default instrument is created

guitar = TunableGuitar()

# It is tuned as a guitar

guitar.tuning([82.41, 110.00, 146.83, 196.00, 246.94, 329.63])

# then a note is created on the guitar

guitar_note_001 = guitar.pluck([None, 7, None, None, None, None], duration=1.0)

(...) # Lots of code

# A new default instrument is created

bass = TunableGuitar()

# it is tuned as a bass (with a mistake)

guitar.tuning([41.203, 55, 73.416, 97.99])

(...) # Lots of code

# then a new note is created on the guitar

guitar_note_042 = guitar.pluck([2, None, None, None, None, None], duration=1.0)

Upon closer examination, we can notice that the second .tuning() method was called on the wrong instrument. Consequently, the sound produced by guitar_note_042 is incorrect, but the root cause lies in a different line of code. Identifying such bugs can be time-consuming and challenging.

In a stateful API, it is easy to accidentally modify the state (i.e., the values of internal self attributes) without realizing it, especially when copy-pasting lines of code.

The implementation of TunableGuitar() is as follows:

class TunableGuitar:

def __init__(self):

self.st = None

def tuning(self, strings_tunings: list):

self.st = []

for tuning in strings_tunings:

self.st.append(GuitarString(tuning))

def pluck(self, frets: list, duration: float):

note = create_base(duration)

for i, fret in enumerate(frets):

if fret is not None:

note += self.st[i].pluck(fret, duration)

return note

One issue with this implementation is that the initialization __init__() method creates a object without strings. The user must learn to use once the .tuning() method before .pluck(). A careless implementation can leave room for broken objects, i.e. whose internal state is messed up.. You can read more about this with this notebook dedicated to desynchronized objects.

However, a stateful object is often necessary. The key is to ensure that its statefulness is both explicit and natural to the user. On the other hand, If you want to stay on the safe side, read about Immutable Data Classes, a very safe storage for your data : attributes are set in stone at the initialization and cannot change afterward.

Choosing the wrong audience

In our scientific computing domain, object-oriented concepts are not typically ingrained in the audience’s culture. However, a developer well-versed in OOP may utilize inheritance in their API, such as the pre-tuned GuitarInstrument and BassInstrument classes inheriting from the StringInstrument class:

guitar = GuitarInstrument()

bass = BassInstrument()

g_001 = guitar.pluck([None, 7, None, None, None, None], duration=1.0)

b_012 = bass.pluck([2, None, None, None], duration=1.0)

This approach eliminates the need for manual tuning, offering simplicity and convenience. Let’s examine the implementation:

class StringInstrument(ABC):

def __init__(self, strings_tunings: list):

self.st = []

for tuning in strings_tunings:

self.st.append(GuitarString(tuning))

def pluck(self, frets: List, duration: float):

note = create_base(duration)

for i, fret in enumerate(frets):

if fret is not None:

note += self.st[i].pluck(fret, duration)

return note

class GuitarInstrument(StringInstrument):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__([82.41, 110.00, 146.83, 196.00, 246.94, 329.63])

class BassInstrument(StringInstrument):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__([41.203, 55, 73.416, 97.99])

While this design functions well for those familiar with OOP and Python, individuals lacking a strong understanding of OOP may find elements like ABC, super, and the nested GuitarInstrument(StringInstrument) confusing. There is worse : creating a new instrument, such as a UkuleleInstrument, is accessible only to those well-versed in OOP.

Furthermore, this example highlights another code smell:

guitar = GuitarInstrument()

guitar2 = GuitarInstrument()

guitar3 = GuitarInstrument()

Here, all instances of the object are identical, raising concerns about the redundancy and lack of uniqueness within the API.

Further reads

Object-oriented programming encompasses a vast and diverse field with numerous valuable resources available. If you’re looking for a comprehensive, yet general introduction, the Educative intro can be a helpful resource. For a more Python-focused content, you can begin with RealPython’s introduction.

When it comes to the Dos and Don’ts of OOP, these principles were distilled by Robert C. Martin into 6 STUPID concepts and 5 SOLID concepts, which are outlined as follows.

STUPID concepts in OOP

The STUPID concept is an acronym that highlights certain pitfalls and anti-patterns that can arise in object-oriented programming (OOP). Each letter in STUPID represents a specific issue:

S - Singleton: The overuse of singletons can lead to tightly coupled code and difficulties in testing and maintainability.

T - Tight Coupling: Excessive dependencies between classes can make the code less flexible, making it harder to modify or extend.

U - Untestability: Poor design choices in OOP can result in code that is difficult to test, leading to decreased code quality and reliability.

P - Premature Optimization: Optimizing code prematurely can lead to complex and hard-to-maintain designs without providing significant performance improvements.

I - Indescriptive Naming: Poorly chosen or ambiguous names for variables, methods, and classes can make the code harder to understand and maintain.

D - Duplication: Code duplication violates the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle and can lead to maintenance issues and inconsistencies.

The STUPID concept serves as a reminder to avoid these common pitfalls in OOP design and development to ensure more maintainable, flexible, and testable code.

Solid Concept in OOP

The SOLID principles are a set of five design principles that guide software developers in creating maintainable and flexible object-oriented code. Each letter in SOLID represents a specific principle:

S - Single Responsibility Principle (SRP): Each class or module should have a single responsibility, meaning it should have only one reason to change.

O - Open/Closed Principle (OCP): Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension but closed for modification, allowing for new functionality to be added without modifying existing code.

L - Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP): Objects of a superclass should be substitutable with objects of its subclasses without affecting the correctness of the program.

I - Interface Segregation Principle (ISP): Clients should not be forced to depend on interfaces they do not use. Instead, interfaces should be tailored to the specific needs of the clients.

D - Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP): High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions. Additionally, abstractions should not depend on details; details should depend on abstractions.

The SOLID principles promote modularity, reusability, testability, and maintainability in OOP. By adhering to these principles, developers can create code that is easier to understand, extend, and maintain, leading to more robust and flexible software systems.

Takeaways

After reading this, here are the key takeaways to remember:

- Always work with a partner-in-crime : someone who can try and comment the interface you are proposing, someone ready to put his/her name on the documentation as “supporter”. Never, ever, develop an object alone.

- Prioritize understanding how your code will be used before implementing it. Consider the typical user, their programming background, and the specific situations the code should handle.

- In simpler scenarios, low-level functions are often more effective than advanced specialized objects. It’s beneficial to have both options available.

- Be cautious of stateful behavior in your code. It is much easier to limit stateful possibilities than to add safety nets.

- Avoid the temptation of over-engineering your code beyond what is strictly necessary here and now. Going beyond critical requirements will make the code harder to learn, use, debug, and impede the overall evolution of the codebase.

Parts of this text were corrected or reduced using a LLM.