Introduction

There is a weekly code review at COOP. There, where we talk only about coding. A chronicle of code reviews would not be edible. Instead, this document curates our present approach on several recurrent topics.

But first you should read Quantified code’s python anti-pattern.

We try to avoid the code smells of STUPID principles:

- Singleton

- Thigh Coupling

- Untestable

- Premature Optimization /and Primitive Obsession

- Duplication

We try to comply to the SOLID principles

- Single responsibility

- Open/Closed

- Liskov substitution

- Interface segregation

- Dependency inversion

You can read further about this in from STUPID to SOLID. If you think you need advice from refactoring seasoned specialists, we encourage you to read from time to time the code smells section of Sourcemaking

Refactoring

Deprecation warning

When a piece of code is deprecated, you must clearly advertise it. Here is the Snippet of Proxy-H5 in Opentea:

import warnings

...

warnings.simplefilter("ignore")

msgwarn = "ProxyH5 is deprecated, move to hdfdict for h5 quick access"

warnings.warn(msgwarn)

print(msgwarn)

True enough, the print() here is a bit overkill because it will pollute any standard output.

However this very deprecation is still nagging at up since 2 years now, showing this print() was not enough to make us clean our mess.

Change without introducing regressions

Sometimes we fight with a clunky object, and we find a better way to do it. The new version is therefore not reverse-compatible with the former. How to make a clean change? Example needed.

The function calculate_profile() from pyAVBP is computing profiles on cuts.

However the signature is just huge:

def calculate_profiles(

solution_paths,

solution_prefix,

shell_params,

bnd_angles=None,

fuel=None,

starting_time=0.0,

ending_time=None,

decorrelation_time_step=None,

distrib_law="normal",

level_of_confidence=0.95,

):

...

# - Infers a `shell`, defined by `shell_params`but also a list of file loosely defined by `solution_paths` and `solution_prefix`.

...

# - Interpolates the data of solution on the `shell`.

...

# - Create a lot of results by averaging in many directions the interpolation.

...

return profiles

This is because the function is doing too many things. We separate this into two decoupled functions:

def infer_shell_from_cuts(

paths,

prefix,

shell_params,

bnd_angles)

...

# - Infers a `shell`, defined by `shell_params`but also a list of file loosely defined by `solution_paths` and `solution_prefix`.

...

return shell

and

def calculate_profiles_on_shell(

shell,

solution_paths,

solution_prefix,

fuel=None,

starting_time=0.0,

ending_time=None,

decorrelation_time_step=None,

distrib_law="normal",

level_of_confidence=0.95,

):

...

# - Interpolates the data of solution on the `shell`.

...

# - Create a lot of results by averaging in many directions the interpolation.

...

return profiles

To keep the initial function calculate_profiles() running without being a dead weight,

we replace the content, and add a deprecation warning:

def calculate_profiles():

warnings.warn("calculate_profiles() is deprecated, prefer calculate_profiles_on_shell()")

shell = infer_shell_from_cuts()

calculate_profiles_on_shell()

By doing so you can keep all the former calls available, with a proper deprecation policy, and without code duplication.

Developing

Fetching info in large data trees

We created a full package for this very purpose. Read more in fetch information from large datatrees.

StateFull or StateLess code

This section features now its own post : [stateful vs stateless](Layered IP

Unnecessary “else” after “return” (no-else-return)

This one is a bit tricky. We recommend the reading of this post on Else after return. As a rule of thumb, try to comply to pylint and use implicit else, and if you end up with something too cryptic, go explicit. This element is also mentioned the basics on python function, a good-to-re-read essential.

Values of optional arguments must be immutable

This seems a bit high level for beginner Python devs, but it is quite important as it can lead to annoying bugs. Let’s look at an example. Say we make a function that appends a 1 at the end of a list:

1 2 3 4 | def append_one(start=[]):

"Add a [1] at the end of a list"

start.append(1)

return start

|

Cool… So, now, the output of a call to append_one() should be simply [1]. How about if we call it twice?

1 2 | print(append_one()) # [1]

print(append_one()) # [1, 1] ???

|

What the heck just happened? Well, we said you weren’t supposed to use a mutable (e.g. []) as value of an optional argument, and this is why! In practice, the function signature (it’s name and inputs) is read by the interpreter once, when it reads the file, and start is associated to a list. When you call the function again, the same list is still the value of the optional argument. But this is not what we had in mind! Let’s use an immutable argument instead:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | def append_one_bis(start=None):

"Add a [1] at the end of a list"

if start is None:

start = []

start.append(1)

return start

print(append_one_bis()) # [1]

print(append_one_bis()) # [1]

|

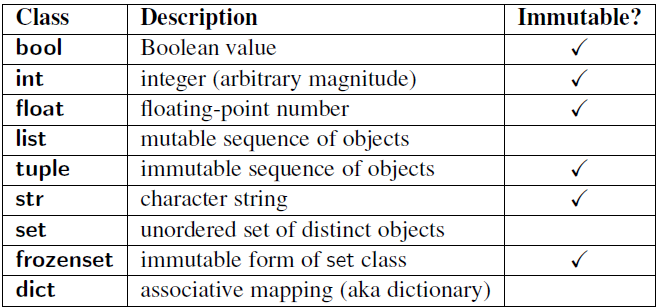

Now that’s much more like it! So the takeway here is simple: Don’t use mutables as values for optional agruments! And if you don’t remember what’s immutable or not in Python, here is a nice cheetsheet (checkout the related article too):

DataClasses

Data classes are Read-Only object to store data. A Read-Only object reduces the mental fatigue, good for you.

The Official dataclasses

Data-Classes are a great idea described in PEP_0557 then introduced as a core utility since Python 3.7.

There is a backport in Python 3.6 with PyPI dataclasses. Watch this video on dataclass and attr for an expert 7min lecture.

Follows some lousy beginners attempts - not recommended yet.

NamedTuple emulation

You can use a NamedTuple as a replacement :

from typing import NamedTuple

class Obstacle(NamedTuple):

"""Define an Obstacle object.

shape: str, either None, cylinder or rectangle

dim1: float, either None or meters

dim2: floar, either None or meters"""

shape: str = None

dim1: float = None

dim2: float = None

Read/Only Class

You can also disable any edition of the attributes of your Class.

class Obstacle:

"""Define an Obstacle object.

"""

def __init__(

shape,

dim1,

dim2

):

"""

shape: str, either None cylinder or rectangle

dim1: float, either None or meters

dim2: floar, either None or meters

"""

self.shape = shape

self.dim1 = dim1

self.dim2 = dim2

def __setattr__(self, *args):

"""Refuse any change of value"""

if inspect.stack()[1][3] == "__init__":

object.__setattr__(self, *args)

else:

raise TypeError(

f"Cannot change {args[0]} attribute : "

"SetupReferenceValues is immutable."

)

Profiling

Micro profiling

The decorator timeit will help to profile single calls of functions:

Global profiling

Use the module cProfile…

> python -m cProfile -o test.prof test.py

> snakeviz test.prof

Snakeviz(https://docs.python.org/3/library/timeit.html) is a python package

The is also this recent pick we found : viztracer which looks promising. For HPC profiling, you can also try out scalene

Profiling line by line

Add this decorator at the beginning of the function you want to profile:

@profile

def hello():

"awesome function"

print("Hello world")

Then to launch profiling:

> kernprof -l script_to_profile.py

And to visualize:

> python -m line_profiler script_to_profile.py.lprof

Python Imports

The Python reference is the official ressource about imports, but there are a lot of intricacies so this post might be an easier introduction.

Intra-package imports

Based on some good quality Python packages (e.g. flask), it seems that for intra-package imports, relative imports are the norm. As an example, suppose your package looks like this:

package/

__init__.py

subpackage/

module.py

And module.py contains func, which we are interested in. From here, suppose you want to give access to func easily from the outside, e.g. via a simple:

from package import func

This can be done by writing the following in the top __init__.py file:

from .subpackage.module import func

This is a relative import. You could also do this via an absolute import:

from package.subpackage.module import func

The __all__ dunder magic

The __all__ variable enables manual specification of the importable names of a module (e.g. via an import *). For example:

"""Awesome module awe.py"""

__all__ = ["func1", "ClassyStuff"]

def func1():

""" Nice function I want to boast about"""

pass

def _func2():

""" Ugly function I keep underneath"""

pass

class ClassyStuff:

""" Nice class I want to boast about"""

pass

Here, from .awe import * would add func1 and ClassyStuff to your namespace. However, because the naming conventions have been followed (i.e. _func2 is private, and its name starts with _), you would get the exact same result without the __all__ statement.

For these reasons, as long as we keep a good naming hygene, it seems we don’t need the __all__ statement.

* imports in __init__.py files

This is something we did a lot at some point, in the spirit of “no code duplication”. Each times modules are updated with a function, the api is naturally updated. However, this also makes the api much less explicit. Instead of purposefully showing everything you get in your namespace in the __init__.py file, you have to execute the module to actually know what’s in the namespace. Generally, this good packages seem to go the explicit route, even if this means some code duplication + possible mistakes when beginners add functions to modules but not to the __init__.py file. We’re on the fence on this, but leaning towards this fully explicit approach.

SOLID - Dependency inversion : a worked example

This time we discussed how we could implement something to edit easily a run_paramsfile for AVBP.

This file look like:

$INPUT-CONTROL

mesh_file = ../../../Documents/MESH_C3SM/TRAPVTX/trappedvtx.mesh.h5

asciibound_file = ./SOLUTBOUND/combu.asciibound

asciibound_tpf_file = None

initial_solution_file = ./INIT/combu.init.h5

mixture_database = ./mixture_database.dat

probe_file = ./combu_probe.dat

solutbound_file = ./SOLUTBOUND/combu.solutbound.h5

species_database = ./species_database.dat

$end_INPUT-CONTROL

$OUTPUT-CONTROL

save_solution = yes

save_average = no

(...)

We tried a dependency inversion related exercise: discuss on the interface we want to show outside. The discussion ended up with 5 ways of implementation:

A function with extensible arguments - F1

out = update_runparams(

"./run.params",

{

"RUN-CONTROL/CFL": 0.4,

"RUN-CONTROL/clip_species": True,

} # comment utiliser ce truc?? Nouvelle syntaxe!

)

with open("./rp_changed.txt", "w") as fout:

fout.write(out)

The dictionary argument is a problem, because you will have explain exactly what the function expects. Not really explicit.

A functional approach - F2

lines_ = open("./run.params", "r").read()

lines_ = update_runparams(lines_,"RUN-CONTROL","CFL", 0.4)

lines_ = update_runparams(lines_,"RUN-CONTROL""clip_species",True)

with open("./rp_changed.txt", "w") as fout:

fout.write(lines_)

The arguments are easier to figure out now, and we can repeat the calls to a function.

However the user must handle the dataflow explicitly, lines_ being both the input and the output.

A class with getters setters - C1

rpm = RunParamEditor("./run.params")

rpm.set("RUN-CONTROL","CFL", 0.4)

rpm.set("RUN-CONTROL","clip_species", True)

#rpm.add("RUN-CONTROL","CFL", 0.4)

#rpm.delete("RUN-CONTROL","CFL")

rpm.dump("./rp_changed.txt")

The feeling is familiar, but the data flow is now implicitly take care of by rpm object.

However, the getter setter is still homemade, and might need more explanations.

A class with a dictionary feeling - C2

rpm = RunParamEditor("./run.params")

rpm["RUN-CONTROL"]["CFL"]= 0.4 # Change

rpm["RUN-CONTROL"]["CFL2"]= 0.4 # Add

del rpm["RUN-CONTROL"]["CFL2"] # Delete

rpm.dump("./rp_changed.txt")

This way the rpm object is edited like a dictionary, the user need only to learn the __init__() and dump() methods.

Back to a functional approach - F3

At this point why cannot we move to a pure dictionary handling?

rpm = runparam_asdict("./run.params")

rpm["RUN-CONTROL"]["CFL"]= 0.4 # Change

rpm["RUN-CONTROL"]["CFL2"]= 0.4 # Add

del rpm["RUN-CONTROL"]["CFL2"] # Delete

runparam_dump_fromdict(rpm, "./rp_changed.txt")

Balance between approaches.

F3 is the easiest to implement, with a very small overhead of customization. It will be however be hard to extend, oppositely to a class. And we already are sure that some extension will be needed to this dev. That is why C2 is probably the best bet for the future.

To consider

- Think about what will go wrong at first before deciding between a function or a class.

- an object will show some advantage when multiple modifications are to be performed

- start with schematizing the functionalities / methods before starting the actual implementation

- AVBP blocks: there are keywords which must be given in order! -> renders it more messy if your python dict does some sorting

- AVBP inconsistency: the POSTPROC block is NOT hashable, several keywords can be repeated. The dictionary way is doomed!